Deus apud Machinas

Meaning in the Digital and Populist Age

In a feisty jeremiad,

responds to a recent viral essay by . Lyons argues that Donald Trump and populism signal the return of the “strong gods” of faith and solidarity neglected at the end of history.As Lyons puts it,

This masculine-inflected spirit of thumotic vitalism was suppressed throughout the Long Twentieth Century, but now it’s back….Instead of producing a utopian world of peace and progress, the open society consensus and its soft, weak gods led to civilizational dissolution and despair. As intended, the strong gods of history were banished, religious traditions and moral norms debunked, communal bonds and loyalties weakened, distinctions and borders torn down, and the disciplines of self-governance surrendered to top-down technocratic management.

Smith agrees with the premise that the “strong gods” have indeed attenuated but doubts that Trump provides much of a remedy. Instead, he claims, Trump II offers performative destruction without creation.

Whether or not one agrees with Smith’s assessment of the new administration, he does offer an important reminder that, in order to succeed, the populist right will actually have to build. It is obviously still early days for the second Trump presidency, but the White House needs to keep an eye on the scoreboard: “lib tears” are no substitute for delivering for working families.

That said, there might be a beartrap lurking within the vitalist account of the “new Right”: the thesis that, at last, people are breaking free of the dead hand of liberal proceduralism and now, finally, “you can just do things.” While insisting on the self-justifying agency of the will may have a certain psychological appeal, it can also lead to catastrophic folly. (That’s one of the principal warnings of so much ancient philosophy, from Plato to Aristotle to Xenophon to Cicero.)

After all, “you can just do things” could have been the motto of the George W. Bush administration. As an anonymous high-level Bush aide told journalist Ron Suskind in 2002, “We're an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you're studying that reality -- judiciously, as you will -- we'll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that's how things will sort out. We're history's actors . . . and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.”

Among some “new Right” theorists, perhaps the singular discrediting act of the old Republican Party was invasion of Iraq (cue the “forever war!” chorus). Yet public defenders of the Iraq War at the time sounded a lot like some “based” social-media anons today, as Tanner Greer noted a few years ago. The War on Terror and the Iraq War would be a chance to restore “manliness” and for the “hairy-chested” heroes of Paul Wolfowitz and Dick Cheney to wrest the country back from “shaved-and-waxed male bimbos.” All those apologetics lacked was a denunciation of the “longhouse.”

I’ve long argued that contemporary populism might not be such an aberration from past conservatism as some populists and their foes claim. There are, for instance, considerable affinities between populism and neoconservatism—and not just because neoconservative icon Norman Podhoretz is a big Trump defender. But that cuts in another direction, too: the “new Right” could end up repeating some of the mistakes of its predecessors. Blowing things up for the sake of some ideological crusade—or even just because you can—can cause a political coalition to reap the whirlwind.

But I want to go back to something else Noah Smith brought up. He agrees with Lyons about why the “strong gods” receded but offers an alternative explanation as to why:

We didn’t abandon those “strong gods” because liberals went too hard on old Adolf. We abandoned them because of technology.

The 1920s saw the beginning of mass affluence in America, along with the creation of technologies that gave individual human beings unprecedented autonomy and control over their physical location and their information diet. Car ownership allowed Americans to go anywhere, any time, freeing them from their ties to a specific place. Telephone ownership let people communicate over vast distances. Television and radio exposed them to new ideas and cultures, and the internet exposed them to even more.

Then came social media and the smartphone. Suddenly, “society” didn’t mean the people in the physical space around you — your neighbors, coworkers, workout buddies, etc. First and foremost, “society” became a collection of avatars writing text to you on a little glass screen in your pocket. Your phone was where you met and conversed with friends and lovers, where you argued about politics and ideas. People’s roots changed from physical space to digital space.

Smith is quite right that technology has been one of the great revolutionary vehicles for modernity. Ideas have consequences, yes, but so do the technological contours within which we live. For instance, where would the sexual revolution be without penicillin and the birth-control pill? I also think it’s undeniable that technological change has contributed to our recent political distemper.

And yet…and yet…and yet…

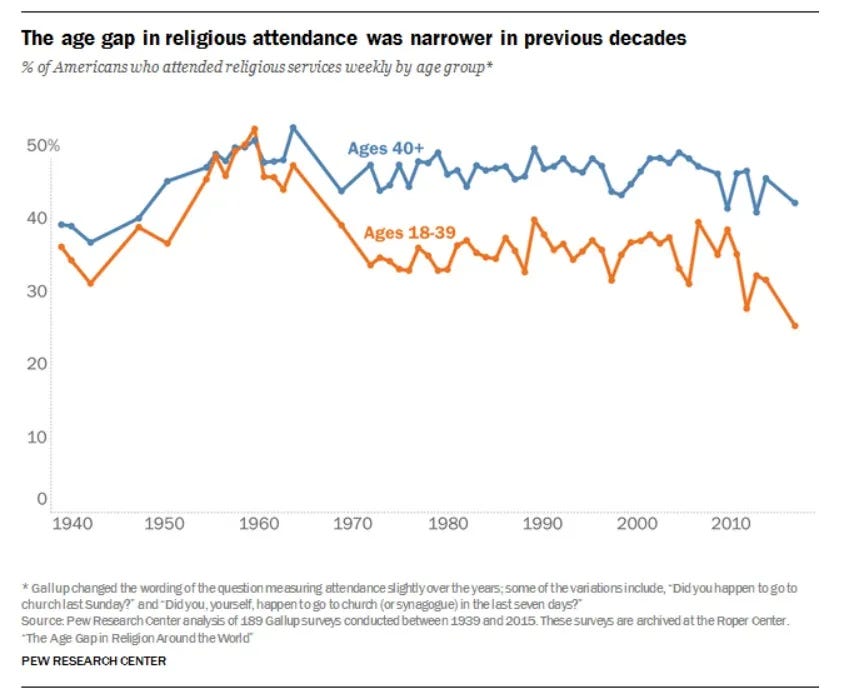

The twentieth century also shows that technological modernization is not incompatible with strong social commitments. Smith rightly observes that social solidarity actually increased in the United States after the Second World War—even with mass affluence and cars and TV and radio and telephones. Two charts he includes show rising religious attendance in the postwar era as well as a boost in social solidarity as Robert Putnam has calculated it.

As others have observed, the Baby Boomers came of age during a time of highly unusual national cohesion compared to historical trends. Increased national diffusion and even some level of national disconnection would be more a return to normal. And a cartons of eggs had to be broken to make that omelet of social cohesion—two devastating world wars, a Great Depression, decades of one-party rule that centralized the economy to an unprecedented degree, and so forth.

Yet that period nevertheless illustrates that we can still find social connection, moral purpose, and religious bonds even within the machine age. On a personal level, we can see how the technologies of the past could be used not to fragment people but to bring them together. The phone meant that you could still talk to your friends and family even after moving to a new city. The train, highway, and airplane made it easier to bring the family together.

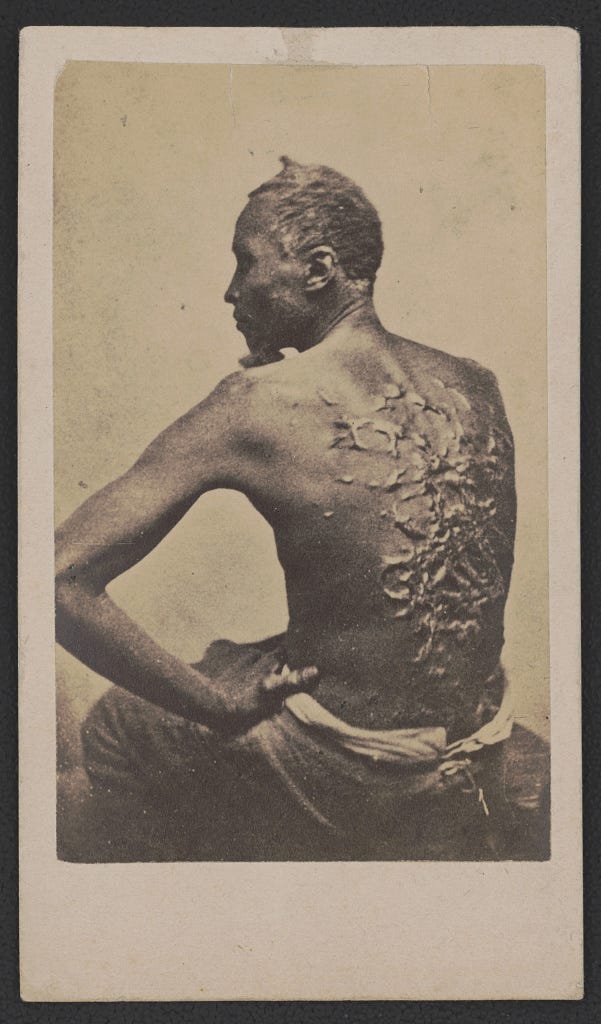

In the nineteenth century, abolitionists used photography and the printing press (that is, technology) to document the humanity of the enslaved and the cruelty of slavery. The scarred back of “whipped Peter” galvanized opposition to slavery in 1863.

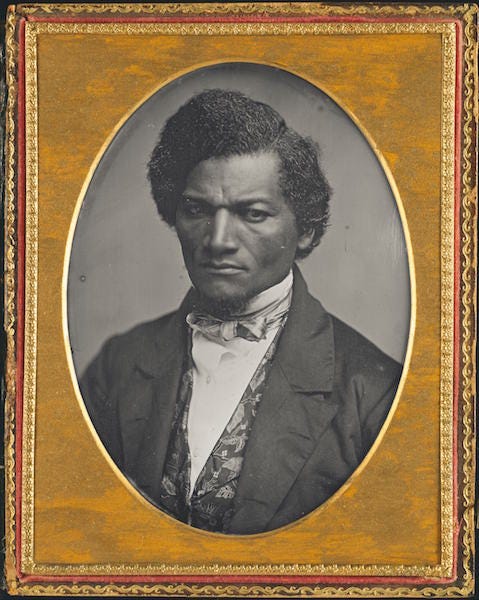

Likewise, there’s a reason why Frederick Douglass—perhaps the most photographed American of his era—sat for so many portraits. Photographic portraiture and Douglass’s landmark autobiographies illustrated the profound dignity of those held (or formerly held) in bondage.

All that is to say that technology can knit as well as divide. It can undermine our humanity but also be adapted to serve human purposes.

That’s true of digital technologies, too. While remote work has certain drawbacks, it can also be a way of spreading economic opportunity beyond NYC/DC/SF and helping working families. I know some at least a few people who are able to work remotely part-time and be stay-at-home parents. Perhaps one of the biggest resources for artisanal culture over the past decade (homegrown chickens, handmade clothes, and so forth) has been the Internet.

This suggests that we are not fated to atomistic disconnection as technology progresses, but it also means that we need to think critically about how to direct technology toward the ends of human flourishing. The recent manifesto “A Future for the Family: A New Technology Agenda for the Right” picks up this very theme: “A new era of technological change is upon us. It threatens to supplant the human person and make the family functionally and biologically unnecessary. But this anti-human outcome is not inevitable. Conservatives must welcome dynamic innovation, but they should oppose the deployment of technologies that undermine human goods.”1

Our disenchantment is not total, and technology policy rightly understood has to take into account our natural capacities for service, wonder, and human connection.

See also this new essay by Jon Askonas on the important project of leveraging technology for the American family.