What political “enabling” is really about. Links on the defense industry, fusionism, AI, and more…

Enabling is one of the most charged words in American politics today. Donald Trump’s foes regularly accuse other Republicans, conservative columnists, and the GOP electorate of enabling him. Yet Trump’s foes may themselves often be his greatest “enablers” and have created the conditions for his disruptive ascent.

As a sign of the way that “enabling” discourse has permeated American politics, consider this much-shared New Yorker essay by Adam Gopnik on Timothy W. Ryback’s Takeover: Hitler’s Final Rise to Power. The print headline of Gopnik’s essay is simply “The Enablers,” and, according to Gopnik, much of the blame for Adolph Hitler falls upon the shoulders of the German normie right, which at first thought it could coopt him but eventually was thoroughly marginalized. These “establishment enablers”—the ranks of which include politicos as well as the head of a media empire—proved important allies of the Nazis. Thus, “the decent right thought that he was too obviously deranged to remain in power long, and the decent left…thought that, if they forcibly struck to the rule of law, then the law would somehow by itself entrap a lawless leader.”

Though Gopnik does not draw the parallel overtly, many on social media have found this an allegory for the Trump years. In successive primary campaigns, Trump has outmaneuvered the Republican establishment of the past (which, having been routed, can perhaps now become the “decent right” to New Yorker readers), and his defeat of Hillary Clinton in 2016 has scarred the psyche of the political left.

While he defers drawing this direct connection, Gopnik’s conclusion certainly seems to hint in that direction:

We see through a glass darkly, as patterns of authoritarian ambition seem to flash before our eyes: the demagogue made strong not by conviction but by being numb to normal human encouragements and admonitions; the aging center left; the media lords who want something like what the demagogue wants but in the end are controlled by him; the political maneuverers who think they can outwit the demagogue; the resistance and sudden surrender. Democracy doesn’t die in darkness. It dies in bright midafternoon light, where politicians fall back on familiarities and make faint offers to authoritarians and say a firm and final no—and then wake up a few days later and say, Well, maybe this time, it might all work out, and look at the other side!

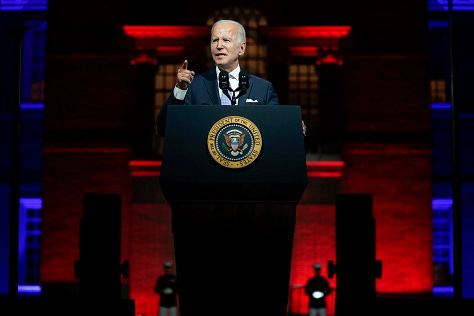

And here the allusions unfurl. There’s the way Trump scorns the normal guardrails of public discourse and the way that “look at the other side!” has so often been used to rationalize norm-breaking in contemporary American politics. The oldest president in American history, Joe Biden could certainly seem the Botoxed embodiment of the “aging center left.”

Yet historical parallels can often distort more than they reveal. There’s something soothing about Gopnik’s narrative for many center-left readers. Hitler’s opponents on the left were simply too nice. They “acceded to Hitler’s ascent with the belief that by respecting the rules themselves they would encourage the other side to play by them as well.” Hitler’s wily brutality overwhelmed this tepid proceduralism.

Many partisans on the left might feel a thrill at the idea that Democrats have not fought hard enough against Donald Trump and all his works. But Democrats have hardly “respected the rules themselves” in responding to Trump. In the years before they became scandalized by “election denialism,” Democrats mounted efforts to challenge the counting of electoral votes in 2001, 2005, and 2017. Progressive outlets devoted themselves to conspiracy theories about how the 2016 election was somehow “hacked.” In the miserable summer of 2020, many center-left institutions promulgated apologia for mob violence in the streets, and an anti-Trump organization laid out a “simulation” in which Biden would provoke a secession crisis if he lost the election. Kyrsten Sinema and Joe Manchin were the only Senate Democrats who stood against the nuclear option in the Senate (a detonation favored both by Trump and his supposed opponents). For her independence, Sinema was driven from the Democratic Party, and Manchin also has announced his retirement from the Senate.

Yet it is not simply that Democrats have shown hypocrisy in responding to Trump’s norm-breaking with their own. They have also systemically elevated Trump as the leader of the Republican Party. The realities of negative partisanship mean that, when Joe Biden delivers a speech attacking Donald Trump and “MAGA Republicans,” he is boosting the stock of both Trump and MAGA with Republican voters.

This is part of a broader strategy. In multiple election cycles, Democrats have intervened in Republican primaries to help nudge Trump-branded Republicans over the finish line. In many cases, these political gambles have paid off for Democrats, but there is a fundamental mismatch between saying that MAGA is a threat to democracy itself and trying to elevate MAGA candidates because of their political vulnerabilities. The October purge of Kevin McCarthy exemplifies this political dynamic: By voting lockstep with a splinter group of Republicans to remove McCarthy, House Democrats knowingly gave the most disruptive members of the Republican conference maximal leverage over the House.

On a deeper level, much of the “enabling” discourse about Trump misses what fundamentally has enabled his rise. Trump is a master of the politics of suspicion, and a deeper public discrediting has helped make him perhaps the focal point of American politics for almost a decade. The obvious cynicism of many of Trump’s opponents—simultaneously comparing him to Hitler and trying to assure his prominence—only adds to the suspicion of many Americans that contemporary politics is fundamentally hollow. While many of Trump’s supporters may take him seriously but not literally, many of his opponents do not take their own arguments seriously at all.

The past year indicates how constitutional hardball to oppose Trump in fact “enables” him. The unprecedented legal campaign against Trump transformed the dynamic of the 2024 Republican primary and catapulted him to an enduring polling lead with GOP voters. The attempt to use the 14th Amendment as a roving vehicle of electoral disqualification was unanimously rebuffed by the Supreme Court—again, in a way that played into Trump’s hands.

Much more than any talk-show host on cable, Joe Biden himself has continually “enabled” Trump. In choosing immigration policies that have helped precipitate a crisis on the border, Biden has given Trump an incredible political opening. His social policies provoke wariness among working-class voters and may potentially imperil some of his industrial-policy efforts.

While much of the American commentariat remains enamored with the tropes of the 1930s, the United States is not Weimar Germany. It has not lost a devastating world war. It has established constitutional institutions. If its situation differs, so too might the challenges it faces. Elite polarization threatens orderly workings of power—with potentially devastating implications for American international commitments. Decades of globalization have changed the international and domestic playing fields. A digital revolution has transformed households and the public square.

In part because Trump is a highly polarizing figure, it’s easy to focus simply on him—with either adoration or opprobrium. But his rise points to those deeper issues. The fixation on the Trump Show has let those underlying issues continue to simmer. And the promotion of radical measures to “resist” Trump has ended up normalizing some of his own most disruptive efforts. Far from offering a way forward, the reductio ad Hitlerum may in fact be one of the great enablers of constitutional decay.

Other links:

A report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies on the growing industrial power of the People’s Republic of China.

Marco Rubio on industrial policy for National Affairs: “Using government to support industry and defend our economic and national security is nothing new for America, nor is it a departure from American conservative principles. And despite assertions from critics that free markets alone are responsible for America's success, plenty of evidence indicates that industrial policy played a vital role in building our nation into a world power.”

At FUSION, a bang-up survey of debates about “fusionism” (that is, the fusion of market economics and social conservatism—though even that is disputed). Notable contributions include Aaron Renn (is fusionism an anachronism?), Donald Devine (who worked for Reagan) on the challenges of rationalism, Stephanie Slade on the philosophical roots of fusionist thinking, Eugene B. Meyer on virtue and freedom, and Brad Littlejohn on the role of practice for political affinities.

A fascinating conversation between Reihan Salam and Jon Askonas on conservatism and tech policy.

In the sleek, redesigned Modern Age, Lee Edwards returns to the legacy of Paul Weyrich.

A beautiful reflection by David Frum on his daughter Miranda and her adorable dog Ringo. It’s moving meditation on grief and a bright young life lost far too early.

Jean M. Twenge: Smartphones are harming America’s teenagers. “More than twice as many American teens suffered from major depression in 2022 than did in 2011, with nearly all of the increase occurring before the Covid-19 pandemic struck in 2020.”

A deep dive by Stephen Eide on how to reform mental-health treatment in prisons.

Mathis Bitton on the structural challenges of French politics.

ICYMI: I wrote on the democratic challenges of AI for The Atlantic…the political implications of the Biden administration’s Apple lawsuit…Biden’s vibes-based appeal to Haley voters…the limits of a “resistance” political strategy v. Trump…

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed, please consider liking, sharing, and subscribing.