The Colossus and the Yeoman

The Statecraft of Liberty, Continued

(Since the original “statecraft of liberty” post generated some reader interest, I thought I would follow up with another adapted section on political economy: the colossus and the yeoman. With Labor Day coming up, it might seem particularly relevant!)

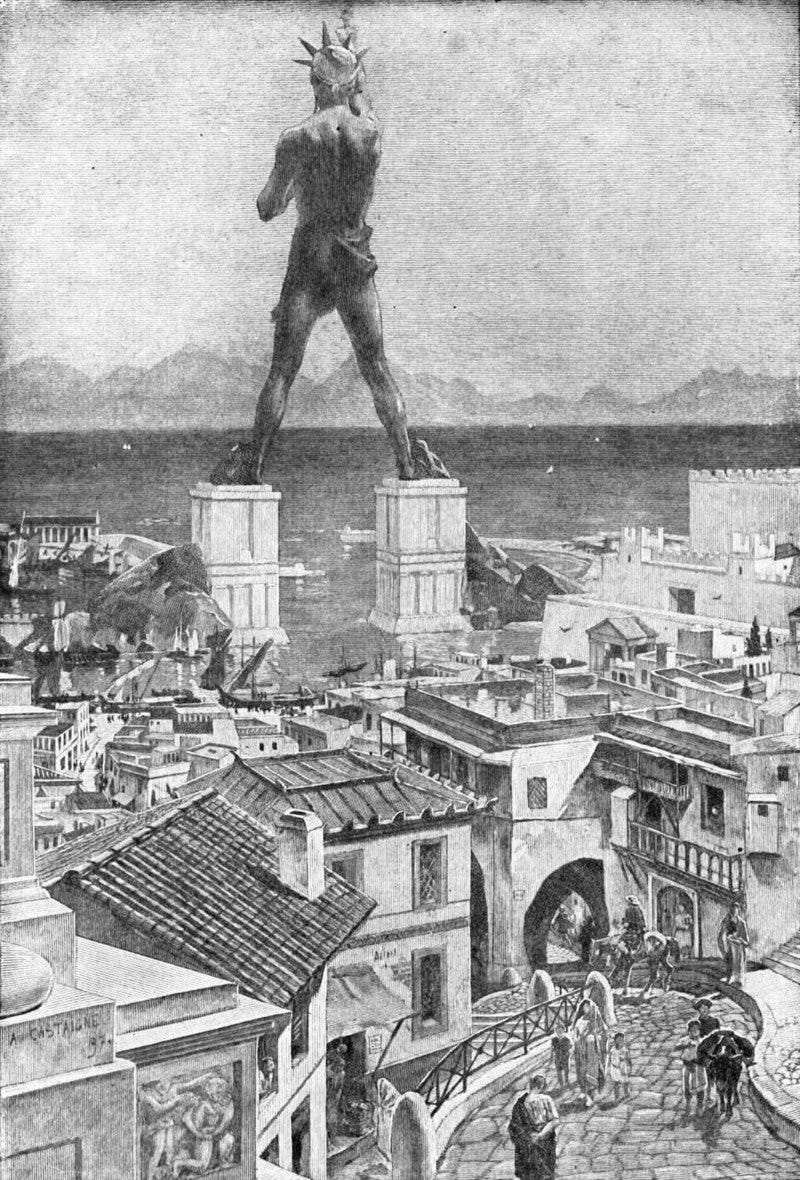

The colossus and the yeoman haunt American approaches to political economy. The colossus stands for power, bigness, and concentration. It is Wall Street, skyscrapers, and billowing smokestacks. The figure of the yeoman instead embodies the tradition of diffusion and egalitarianism: the family farm, the small town, and the nicked kitchen table. That duality of the colossus and the yeoman might be restated as the rivalry between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson. Both traditions have shaped American life, and each illuminates some of the underlying questions of statecraft.

The shine of the colossus is the appeal of organized, consolidated power. In “Report on the Subject of Manufactures,” Hamilton associated manufacturing power with political sovereignty: “the independence and security of a Country, appear to be materially connected with the prosperity of manufactures.”1 A project of greatness and opulence would demand the cultivation of industry. The steam engine, the oil rig, and nuclear powerplant could allow for the harnessing of energy. What Henry Clay called the “American system” in the nineteenth century used tariffs and infrastructure programs to encourage commercial development. Under the aegis of the great machine, railroads and then highways spread across the continent.

The seething metropolis is the emblem of the colossus. A cynosure for the ambitious and talented, the city throbs with commercial innovation.

Cities are dens of dazzling inequality, where the homeless heroin addict huddles under a cardboard box in the shadow of a billionaire’s penthouse. Hubs of finance and industry of necessity produce great disparities. The technical innovations and market infrastructure that allow for sprawling corporations will also allow the captains of those corporations to enjoy great opulence.

The advantages of the heights are obvious. Since antiquity, cities have been the loci of commercial and political power: Chengdu, Memphis, Athens, Rome. Great empires and kingdoms grew outward from there. Contemporary metropolises—London, Paris, Tokyo, New York, Mexico City, San Francisco, and elsewhere—are important hubs for commerce and innovation. Being a great power on the world stage almost invariably demands great cities, too. Strategic advantages also follow from large corporations. The size of such corporations allows them to invest in innovations and to shape the very contours of the marketplace. In the twentieth century, corporate behemoths had the resources to pour into basic research and the application of this research. AT&T’s Bell Labs minted one technical innovation after the next, from the transistor to computer languages. Magnitude produced not only opulence but technological revolution. Today, the United States enjoys considerable strategic advantages because it is the home of the corporations that have shaped the digital economy (such as Google and Microsoft).

The colossus can thus help promote political vitality. It also appeals to ambition. Those with an appetite for glory will often search for the highest stage. A nation with teeming cities and swelling corporations can thus offer hope—or at least incentive—to ambitious members of its populace. Ambition is not the peak of greatness or virtue, but it is a political reality, and vibrant political regimes have to address it.

Building the colossus requires a vast industrial infrastructure. That industrial might, too, helps secure the vitality of a political regime. In the modern age, technological power has been an essential component of military success, and warfare has been a great accelerant of technologies. An agrarian regime of small householders would be at continued risk of invasion and domination by foreign industrialized powers.

In contrast to the colossus, the tradition of the yeoman emphasizes diffusion rather than concentration, equality rather than magnitude. In a 1785 letter to James Madison, Thomas Jefferson contrasted France (where he was serving as a diplomatic envoy) to the United States. Jefferson claimed that the “property of [France] is absolutely concentrated in a very few hands.” This concentration led to a sprawling servant class and vast unused lands (which were preserved for the hunting of the nobility). In order to redress this concentration, Jefferson said that “legislators cannot invent too many devices for subdividing property.” Inheritance laws would be one mechanism for encouraging this broader distribution. Jefferson wrote that “the descent of property of every kind therefore to all the children, or to all the brothers and sisters, or other relations in equal degree” should be encouraged.2 In the early years of the American republic, state legislatures banned primogeniture and entail in order to encourage a more equal “balance of property” in the words of a Delaware statute.3

Jefferson also argued that a progressive tax system could help promote this diversification of property: “to exempt all from taxation below a certain point, and to tax the higher portions or property in geometrical progression as they rise.” Proponents of a progressive income tax and an estate tax in later years would echo this point about using the taxation system to avert the formation of some hereditary aristocracy. In 1910, Teddy Roosevelt (himself a scion of a distinguished family) defended a progressive estate tax because “the really big fortune, the swollen fortune, by the mere fact of its size, acquires qualities which differentiate it in kind as well as in degree from what is possessed by men of relatively small means.”4

This “Jeffersonian” skepticism of concentration can be seen throughout American life. The fondness for “small town” life and hostility to “big business” (“big” having negative connotations here) are hallmarks of this tradition. This so-called “Jeffersonian” tradition can be seen in Andrew Jackson’s war on the Second Bank of the United States, antitrust reformer Louis Brandeis’s lamentation of the “curse of bigness,” and preferences for localism and federalism in government.5

As with the colossus, the yeoman’s position has its own logic. Vast corporate empires can in turn threaten the independence of smaller groups or individuals and potentially undermine a democratic political order. The robber-barons of the later nineteenth century led a massive industrial transformation, and the convenience of corporate concentration delivered some advantages to many consumers. But the vastness of those fortunes also threatened to swallow democratic institutions. Corporate titans reduced some state legislatures and members of Congress to mere emissaries. In company towns like Pullman, Illinois, corporate policy determined the contours of living; George Pullman (the head of the company) even selected books for the town’s library and productions for the town’s theater.6

The modern city’s wonders can also be dissatisfactions, if not miseries. The urban boulevard as a place of reinvention can also be a site of alienation and inner exhaustion. In his 1903 essay “The Metropolis and Mental Life,” the sociologist Georg Simmel warned that the thrilling modern city could create the inner rigor mortis of “the blasé attitude,” in “which the nerves reveal their final possibility of adjusting themselves to the content and the form of metropolitan life by renouncing the response to them.” One of the great poets of the modern city, Charles Baudelaire was also one of the most exacting chroniclers of modern dissipation. As he writes in “To the Reader”:

If poison, arson, sex, narcotics, knives

have not yet ruined us and stitched their quick,

loud patterns on the canvas of our lives,

it is because our souls are still too sick.7

The yeoman and the colossus to some extent represent antagonistic impulses. Leveling the playing field is at odds with building gilded monuments. Yet they might also be complements. Together, the yeoman and the colossus can speak to different, yet mutually necessary imperatives, and a statecraft of liberty involves balancing the impulses of equality and glory.

Jefferson himself reveals this potential for synthesis. As president, he took sweeping executive action with the Louisiana Purchase in order to extend the magnitude of the United States. He also repudiated his earlier positions on trade and manufacturing. The British blockades of the War of 1812 were the culmination of long struggles over trade in which the young United States found itself. Suddenly, the foreign imports upon which Americans relied were gone, causing no small economic disruption. Jefferson and others learned from this. In an 1819 letter, he wrote that “experience has taught me that manufactures are now as necessary to our independence as to our comfort” and that those who are “against domestic manufacture, must be for reducing us either to dependence on that foreign nation, or to be clothed in skins, and to live like wild beasts in dens and caverns.”8 Without the industrial colossus, Americans risked either dependence or radical privation.

Countering the risks of foreign dependence or invasion has long been an incentive for policymakers to embrace the colossus. During the Meiji Era (1868-1912), Japan rushed at breakneck speed to industrialize and ensure its own independence. Three great global conflicts of the twentieth century—World War I, World War II, and the Cold War—knocked aside many of the traditional checks and balances in the United States. The president became the new colossus, and the United States even embraced the threat of nuclear terror (aptly names MAD).

As the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Europe, Dwight Eisenhower had climbed to the very top of the colossus. But he was also singularly aware of its risks. In his 1961 farewell address as president, he warned about the dangers of the “military-industrial complex”: “This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence—economic, political, even spiritual—is felt in every city, every state house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society. In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.” Notably, Eisenhower did not call upon his countrymen to deconstruct that complex. It was, he argued, “imperative.” Meeting the challenge of the Cold War demanded the vast mobilization of resources and the creation of a new leviathan. Yet he also saw dangers in the gleam of this nuclear-power colossus. Eisenhower’s statement reveals the mixed nature of statesmanship, which often involves grappling with necessary dangers.

A further irony about the relationship between the colossus and the yeoman is that the colossus has at times been appropriated for the sake of the interests of the yeoman, as Progressives and New Dealers claimed to do. Under the principle that only power can check power, these interventionists supported state and federal efforts to use state power to ensure limits to the concentration of private power. Government regulators could break up monopolies. Minimum-wage measures, collective-bargaining laws (such as the National Labor Relations Act), and armies of government bureaucrats at once consolidated power in the federal government and set the terms for business at all levels. (The fact that these centralized efforts could themselves be captured by private interests is yet another layer in the twilight of politics.)

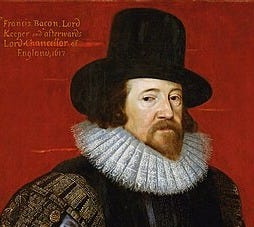

Yet the affinities between the colossus and the yeoman may go even deeper: the yeoman can help build the colossus. In the early modern era, Francis Bacon glimpsed the potential of diffused prosperity for national glory. He elaborates on the benefits of a yeoman prosperity in “Of the True Greatness of Kingdoms and Estates:”

in Countries, if the Gentlemen be too many, the Commons will be base; and you will bring it to that, that not the hundred poll will be fit for a Helmet; especially as to the Infantry, which is the Nerve of an Army: and so there will be great Population and little Strength. This which I speak of, hath been no where better seen than by comparing of England and France; whereof England, though far less in Territory and Population, hath been (nevertheless) an Overmatch; in regard the Middle People of England make good Soldiers, which the Peasants of France do not. And herein, the device of King Henry The Seventh…was profound and admirable; in making Farms and house of Husbandry of a Standard; that is, maintained with such a Proportion of Land unto them as may breed a Subject to live in convenient Plenty, and no servile Condition; and to keep the Plough in the Hands of the Owners, and not mere Hirelings.9

Bacon argued that the military prowess of England came from the relative prosperity of its yeoman. While France had a greater population and range of territory, England had a broader diffusion of wealth—which gave it a military advantage. The plough, he argues, should be in the hands of owners—not “mere hirelings.” By ensuring that average people can have access to ownership, a regime lays the foundation for its own greatness.

Hamilton, Writings, 691-2.

Jefferson, Writings (New York: Library of America, 1984), 841.

See Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution 182-3 and Thomas G. West, The Political Theory of the American Founding, 332-5 on state restrictions on entail and primogeniture. The Delaware statue is quoted in Stanley N. Katz, “Republicanism and the Law of Inheritance in the American Revolutionary Era,” Michigan Law Review 76.1: 14.

Theodore Roosevelt, “The New Nationalism,” The New Nationalism (New York: Outlook Press, 1911), 18.

Louis D. Brandeis, Other People’s Money (New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1914), 162.

Jane Eva Baxter, “The Paradox of a Capitalist Utopia,” International Journal of Historical Archeology 16.4 (2012): 651-665, 656. In Tyranny, Inc., Sohrab Ahmari taps into this tradition of critiquing corporate magnitude.

Translated by Robert Lowell.

Jefferson, Writings 1371.

Bacon, “Of the True Greatness of Kingdoms and Estates,” Essays (London: Bell and Daldy, 1868), 108.

I liked this piece. I wrote a piece about a political typology that tracks with the Hamilton-Jefferson dichotomy you describe. You note that the two sides oppose each other and yet complement each other (sort of a ying-yang). I agree, but did not go with this theme in my political piece since I was trying to establish an analytical framework). It is very true.

https://mikealexander.substack.com/p/an-alternate-american-political-spectrum

Well written But depending on what you're getting at in it, you *may* be inadvertently mischaracterizing the New Deal Era, the USA of the New Deal was still a semi-populist, semi-politically decentralized, semi-economically decentralized, semi-culturally decentralized, and semi-scientifically decentralized system with democratic governance structures built around the old decentralized and publicly accessible mass-member parties. The New Deal Era was far from being the centralized technocratic dictatorships most of us have been taught that it was. There are many demonstrative examples, but to take just a few: Many people have the wrong impression of the TVA, it was not a hyper centralized project with a rigid top down command hierarchy, local business and various grass roots organizations often altered its plans, and introduced new ones or even deleted some of its plans, against the wills of its senior management. Banking and Finance is another great example, most people think that Glass Steagall (Banking Act of 1933) and the Banking Act of 1935 were hyper centralizing, technocratic, and fully products of the New Deal, when in fact the core features of the the system they generated were not created by them, they were just maintained as they had been there for the whole history of the country, such as the interstate banking competition and in-general capital flow inhibitors, and these were extremely populist and done against the wills of Big Finance and the centralizing technocrats. The NIRA, which was the pinnacle of the centralizing technocratic actions wasn't just shot down by the supreme court 2 years after its creation, Congress was likely going to destroy it anyways and may have even been held off on doing so to let the court rule provisions of it unconstitutional; either way it was being successfully resisted all across the country and wasn't going to make it. Despite the president having strong majorities in both houses, the 1930s saw more against the will of the president veto proof majority legislation passes than most of the rest of the countries history combined. States and cities still had very significant powers and purviews. This list goes on and on...