Since I’m based in Massachusetts, someone asked that I write on the election results in the Bay State. I had some free time this weekend, so why not? (To non-Massachusetts readers: Don’t worry, there are some national implications here, too.)

Times have been tough for Massachusetts Republicans, especially at the federal level. Massachusetts has not voted for a Republican candidate for president in 40 years, and it has not elected a Republican to the House in almost three decades. Scott Brown did win a special Senate election in 2010, but he was dispatched in 2012 by Elizabeth Warren. Yet November 5 had some mildly positive news for the Bay State GOP. Like many other strongly Democratic states, Massachusetts edged in the Republican direction. Joe Biden won it by 33 points in 2020, but Harris “only” won it by 25 points. That’s still a pretty big victory margin, but it suggests that Republicans have made up some ground after a brutal few years.

The Mass GOP is still recovering from a political civil war. A few years ago, internal tensions caused a series of unfortunate events for the party. Alienated from the state party leadership, the very popular Republican governor Charlie Baker announced at the end of 2021 that he would not seek reelection, despite a massive war-chest and high approval numbers. The eventual 2022 Republican nominee had the weakest performance of any Republican gubernatorial nominee since 1986, and the GOP felt even more pain downballot. Some offices (like the Barnstable County DA) flipped Democratic for the first time in decades.

Under the new party chair Amy Carnevale, the state GOP has tried to rebuild the party, but that’s a big task. This cycle, the state party made a decision not to contest many races in order to prioritize challenging seats with a retiring Democratic incumbent. This small-ball strategy bore some fruit. Republicans look like they have flipped 3 or so seats in the state legislature. Since Democrats have a supermajority, a flip here and there is the smallest of dents. But it’s still a dent. And Republicans left so much uncontested; the party fielded candidates in only 2 of the 9 U.S. House districts in the commonwealth (independent candidates mounted challengers in two other districts).

Despite its strong Democratic tilt, Massachusetts reflects the broader realignment of American politics. Compare these two maps of the 2000 and 2024 presidential elections:

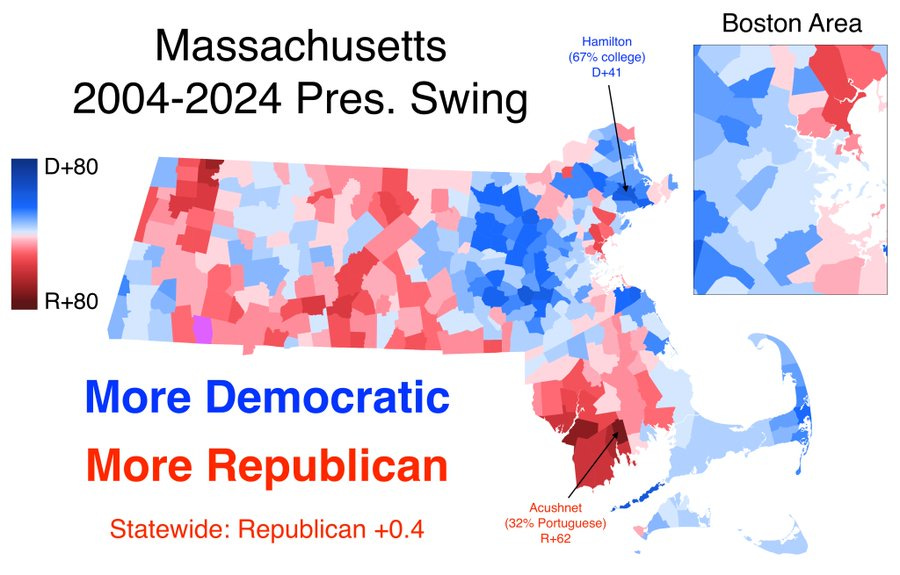

Donald Trump did a few points better in 2024 than George W. Bush did in 2000, but the composition of his map is very different. Since 2000, affluent suburbs have trended more Democratic, but working-class areas have shifted more Republican.

Here’s a map from

on Twitter that visually shows this swing over the past 20 years.This political realignment means that Republicans are now poised to do much better in working-class areas. For instance, Kamala Harris won Carlisle, a super-elite Boston suburb, by 58 points. She actually improved on Biden’s margin there. But Republicans did much better in working-class cities with major immigrant influences, like Lawrence (Harris +17) and Fall River (Trump +3).

There were two “bands” where Republicans kept Democrats to within a 10-point lead: Bristol and Plymouth Counties south of Boston and Hampden and Worcester Counties in the central portion of the state. In both regions, the GOP was buoyed by a strong performance in rural areas and working-class cities. Earlier in the fall, I went apple-picking at a farm near where Bristol and Plymouth County meet, and there were Trump signs everywhere. It was no surprise that Trump ended up winning that town by over 10 points.

Based on all this, Massachusetts Republicans might find that they could build out support from those working-class areas.

Federal races might have some other tea leaves. Despite being a national political brand, Elizabeth Warren underperformed Kamala Harris’s numbers in her reelection race. In the 9th Congressional District in the southeastern portion of the state, longtime incumbent Bill Keating had his weakest reelection performance since the 2014 Republican wave year—winning by only 13 points against “Nurse Dan” Sullivan, a nurse who ran a skeleton campaign.

The ballot questions might also give some clue as to how Bay State Republicans could make inroads elsewhere. Many of the communities in the Boston suburbs swung hard against legalizing psychedelics, and some of the most affluent communities opposed a question that removed passing the state comprehensive educational assessment (MCAS) as a graduation requirement. Running on quality-of-life issues might then be a way for Republicans to help win back some of the suburbs. And that might have implications beyond Massachusetts. As Reihan Salam and others have argued, last week’s election shows the way that concerns about social dysfunction can influence voter decisions at the ballot box.

Massachusetts Republicans have a long way to go to build back their party, but last week’s elections do show some green shoots for the GOP. The Vermont Republican Party has been experiencing a bit of a renaissance under Governor Phil Scott, and it scored some big wins last week, almost doubling its numbers in the state senate. So some renewal could be possible for Massachusetts Republicans—if they can adapt to a changing political landscape.